It’s a common experience. Too much caffeine, anxiety, or insomnia muddled your sleep, keeping you tossing all night. But whatever the cause, the result is the same: The next morning, you feel beat up, achy pain pestering your head, lower back, or joints.

It makes no intuitive sense. How can poor sleep cause pain? But medical professionals have long known there’s a mysterious link between the two, one that’s amplified for those suffering from chronic pain.

“It’s a vicious cycle,” said Weihua Ding, an instructor in investigation in the Critical Care and Pain Medicine program at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and an instructor at Harvard Medical School. Sleep loss heightens pain; pain can cause sleep loss. But why one begets the other has been largely clouded in uncertainty — until now.

In a new study in Nature Communications, Ding and a team of researchers led by MGH identified at least one potential link that locks sleep deprivation and chronic pain in an endless loop. The discovery could lead to a practical solution — a way to sever this link — but it also grapples with a more philosophical question: What is pain, anyway?

“Pain in human beings is a very subjective experience,” said Shiqian Shen, clinical director of the Tele Pain Program at MGH and lead author of the study. “After sleep loss, even if there’s no exaggerated stimulation, we still feel pain. That means something internal is controlling the pain, like a room thermostat controlling temperature.”

Even if some part of our experience of pain is subjective, its consequences are not. About 20 percent of adults in the U.S. experience chronic pain each year, and the issue disproportionately impacts adults who live in poverty, have public health insurance, or didn’t finish high school, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic pain can cause anxiety and depression, forcing people to miss work or social activities. It’s linked to opioid dependence and so contributes to the opioid crisis. And this achy, persistent kind of pain is one of the most common reasons why adults seek medical care.

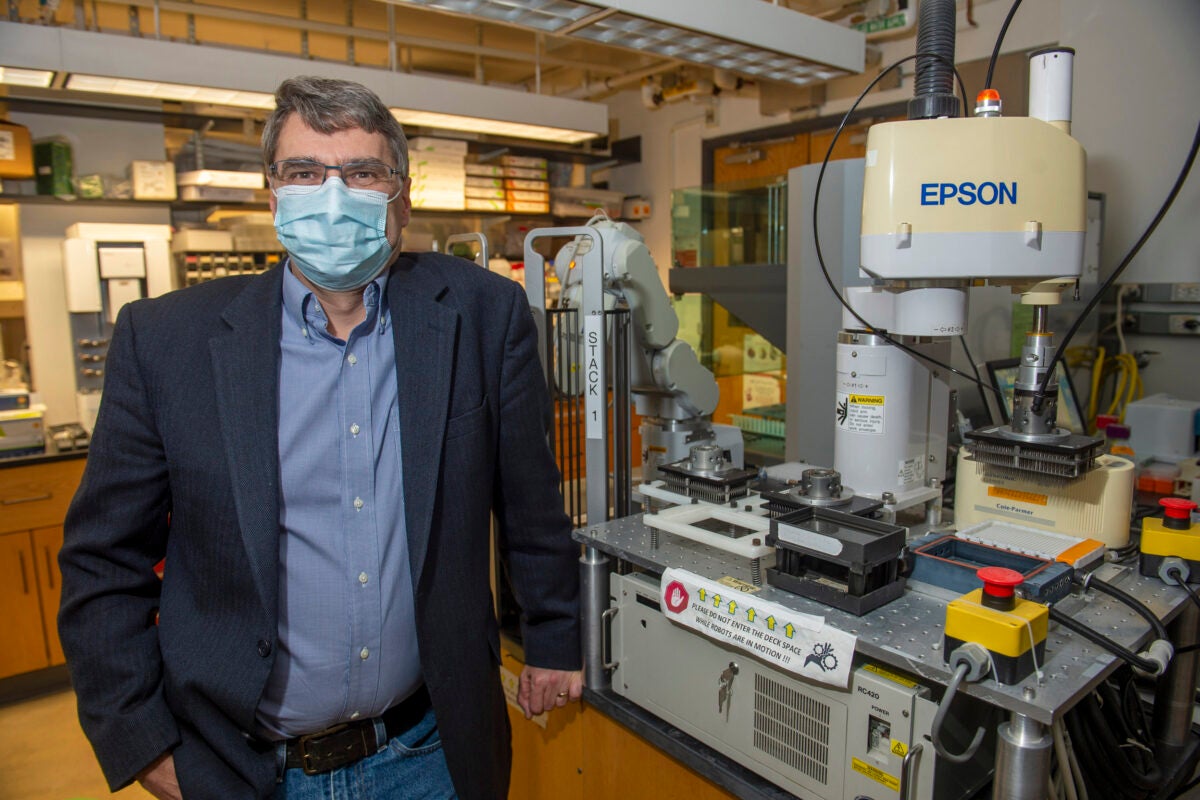

Liuyue Yang (left), Shiqian Shen, and Weihua Ding at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Photo by Dylan Goodman

“Chronic pain medical treatment, social economic burden, and disability costs more than $550 billion per year,” Shen said.

But one little neurotransmitter, known as NADA, could be the key.

NADA, or N-arachidonoyl dopamine, is a type of neurotransmitter called an endocannabinoid, which means it targets a cannabinoid receptor (specifically cannabinoid receptor one) in the brain. These terms might sound familiar to those who depend on medical marijuana to control their anxiety or pain: NADA, the team found, seems to target the same receptor as some marijuana strains, a receptor that appears to help control the body’s perception of pain.

Sleep deprivation — which includes insomnia or even poor sleep quality due to restless leg syndrome or sleep apnea — seems to reduce the brain’s NADA supplies, according to the study. Without enough NADA, we might be in no more pain than the night before but feel it more acutely, so it seems worse. Asked whether that means we’re constantly in a higher state of pain than we realize or that pain is simply an abstract, theoretical concept invented in our brain, Shen said, “I think both are true.”

“Pain is actually a philosophical question,” he said. “In humans, there’s a wide range of suffering.”

Sometimes, Shen explained, the brain interprets one type of pain (emotional distress, for example, or loneliness) as another (say a chronic, persistent ache). And, unlike the acute and temporary discomfort caused by a paper cut, chronic pain can be both unpredictable and relentless. A blinding headache, for example, pulsing nerve damage, or stubbornly sore joints can cause a flood of all kinds of suffering, physical as well as emotional.

“That’s the type of pain that is really most bothersome to humankind,” Shen said. Some humans use that to their advantage: The pain associated with sleep loss is so powerful, sleep deprivation is a common (if heinous) torture tactic. Restrict someone’s sleep, and the pain, perceived or real, is overwhelming — possibly because sleep loss is actually dangerous. If fruit flies don’t sleep for just a few days, they die.

“They essentially burn themselves out,” Shen said. “For people who suffer from chronic sleep loss, or even acute sleep loss, it could be very devastating.” Pain could be a message from the body: Sleep now or pain will be the least of your issues.

Of course, that’s often easier said than done, especially if it’s pain — and not video games or social media or a great book — that’s keeping you up at night.

“Imagine if you can find a way to break the cycle,” said Ding, one of the first authors on the paper. NADA, the team found, could do just that. “This is the first time we’ve discovered this type of metabolite is playing this controlling role in chronic pain and sleep disruption cycles.”

Shen warns that sleep and chronic pain are complex challenges that require complex solutions, including sleep hygiene and mental health treatment. But the biological aspect seems apparent. When the team added more NADA to a deprived system in mouse models, the chemical negated the heightened pain perception caused by sleep loss.

Next, the team plans to explore whether NADA could provide the same analgesic effect in humans. If so, they could design a new, non-narcotic treatment that could manage chronic pain associated with sleep loss or other instigators. They’re also exploring whether they could isolate the component in marijuana that targets the same pain perception receptor. “But that has to be really scrutinized,” Shen said, noting that even if the drug appears to help manage pain it still may prove to be problematic as a treatment. There are too many different strains and too many unknowns.

The team also plans to continue hunting for other underlying causes of chronic pain. But for one team member, first author Liuyue Yang, the connection to sleep deprivation was personal.

“Sometimes, I don’t get enough rest, and the next day, I suffer from a severe headache and back pain,” said Yang, a research fellow at MGH. “I was curious about why this happened. I was just dying to do this research.”